The user experience is how a person feels and responds to using a product, system, or service. A UX designer studies and evaluates the human behaviors and motivations that prompt people to use a product, then draws together all the aspects of a good user experience into a complete package for users.

Behind the design and evaluation of user-centered products are the methodologies, techniques, and deliverables of the UX design process. Joel Marsh, of The Hipper Element, agrees, saying: “Scientific theories are a matter of constructing models through experimentation, which then predict future experimental results. By this definition, UX is a science, not an art.”

Therefore, user experience is a science—just as psychology is a science. But, while the scientific method is great, how do people fit into the mix? Like most things, user experience is subjective. The way people think about and interact with a product influences how they feel about the product and even the brand that owns it.

The UX Design Process

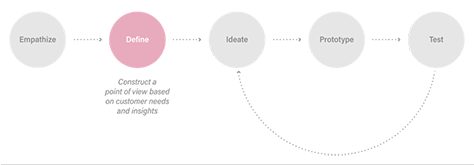

How can we translate the human experience into a reproducible and scientific experiment? By following a UX design process that includes the following steps:

- Strategy—Devise a UX strategy that combines the project’s vision, or goals, and plans for the execution of the design project. For example, one goal might be increasing sales, while the execution of this goal would require assigning resources to the project.

- Research—Conduct research that informs UX design. This UX research might comprehend both internal and external research. For example, you might conduct some fact-finding research, with assistance from your customer-support team, to learn more about common problems that your users encounter; conduct user research to better understand your users’ needs and characteristics; or learn about the strengths and weaknesses of your competitors’ products by performing a competitive analysis.

- Analysis—Analyze the qualitative and quantitative data that comprise your research findings, while keeping your strategy in focus.

- Ideate—Consider many different ideas and concepts—prioritizing quantity over quality—before proceeding with a few UX design options. For example, you might have several different viable ideas for designs to increase signups.

- Prototype—These could be either wireframes or high-fidelity, functional prototypes and are a great way to quickly gather feedback on your design concepts from ideation. You could prototype all your design ideas, iterating on each of them until you’re sufficiently satisfied with your design to move on to testing.

- Test—Conduct UX testing such as usability testing or multivariate testing to better understand what users do and how they do it. You should test and retest as often as necessary. For example, you might be about to roll out a new feature for your application. Create task scenarios, then conduct a moderated usability test to see whether users can discover, access, understand, and use the new feature.

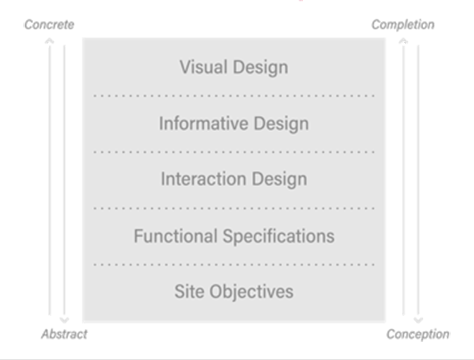

Figures 2, 3, and 4 provide three representations of elements that factor into the UX design process. Figure 2 depicts five aspects of UX design process.

UX Techniques and Deliverables

Table 1 outlines some of the techniques and deliverables for specific phases of the UX design process.

| Phase | Techniques | Deliverables |

|---|---|---|

| Research | Interviews, online surveys, eyetracking analysis, heatmappping, customer-journey workshops, concept mapping | Content inventory, site map; reports or presentations on research findings, usability tests, or analytics; competitive analysis |

| Design | Paper prototyping, wireframing, visual design, interaction design | Flowcharts, functional specifications, static wireframes, paper prototypes, interactive prototypes, high-fidelity mockups, style guides, pattern or component libraries |

| Testing | Moderated and unmoderated usability testing, focus groups, online surveys, A/B or multivariate testing, tree testing, first-click testing | Reports or presentations on research findings, usability tests, or analytics; a findings and recommendations matrix, revised high-fidelity mockups, release plans |

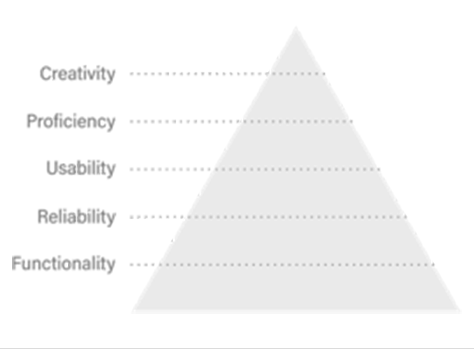

The Design Hierarchy of Needs

Speaking of science and psychology, most people are familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which states that humans have five types of needs they must meet: physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. As human beings, we have the ability to meet our own needs through actions such as buying a home or selecting a partner, but our ability to fulfill our own needs depends on our motivation to do so. Certain needs—such as physiological needs—must be met before we can move up the hierarchy and achieve self-actualization.

A design solution must meet certain basic user needs before addressing others that have a higher perceived value. … To create a successful design and provide a maximal user experience, you must first fulfill the user’s need for functionality….

According to Stephen Bradley’s Design Hierarchy of Needs, a design solution must meet certain basic user needs before addressing others that have a higher perceived value. Therefore, to create a successful design and provide a maximal user experience, you must first fulfill the user’s need for functionality—which lies at the bottom of the hierarchy, indicating that it has great importance, but the least perceived value—then reliability, usability, proficiency, and ending with creativity. In the following list, the perceived value of these design needs ranges from low to high.

- Functionality—Lowest value—A design should be functional and fulfill its purpose. For example, an email application must be able to send an email message to a recipient.

- Reliability—Low value—A design should be consistently reliable and behave as expected every time. Continuing with the email example, the recipient will receive the email message that the user sends every time.

- Usability—Medium value—A design should facilitate users being able to easily accomplish their task. How easy is it for the user to compose an email message? Does the user know where to enter the recipient’s address? Can the user easily send the message?

- Proficiency—High value—A design solution should make users feel empowered and able to improve their own life. When a user is sending an email message, allowing multiple recipients empowers the user to communicate with multiple people and save time by writing the message only once. The user can also create groups—including family members, work colleagues, or friends—then send an email message to a group.

- Creativity—Highest value—A design can support users’ needs in unique and innovative ways—for example, by supporting automated interactions or enabling users to create their own templates. Users might want their email application to use their own custom designs for email messages. They might also want to create their own auto-response messages rather than just using a standard response.

Figure 3 shows this design hierarchy of needs.

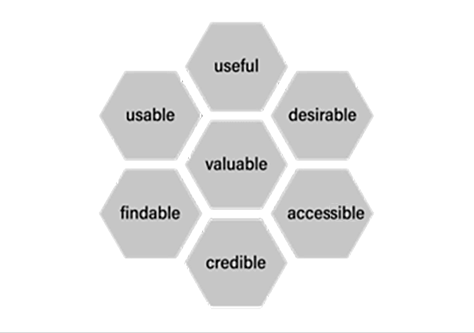

The User Experience Honeycomb

Peter Morville of Semantic Studios created the User Experience Honeycomb, shown in Figure 4, which covers the various facets, breadth and depth, and subjective considerations of UX design. When you’re defining the strategy for a UX design project, use the UX honeycomb to consider what product characteristics are potential priorities.

When you’re defining the strategy for a UX design project, use the UX honeycomb to consider what product characteristics are potential priorities.

- Useful—Products and systems should be useful and fulfill the user’s wants and needs.

- Usable—Products and systems should be easy to use.

- Desirable—Design elements must be visually attractive, easy to interpret, and consider emotional design.

- Findable—Information should be easy to find and navigate.

- Accessible—A design solution should be inclusive of all people with disabilities.

- Credible—A design should encourage users’ positive feelings about and trust and belief in a product or service.

- Valuable—Products and services must deliver measurable value, so you should consider metrics such as sales volume and customer satisfaction.

So What Is User Experience—A Science or an Art?

When you do UX strategy and research correctly, you’ll ultimately be able to control the elements and the outcomes of UX design. When you’re able to predict what will happen based on science and analytics, you can create better designs. The outcomes of your experiments will be more predictable because you know you’re doing something right. And, if they fail horribly, you’ll more than likely have a good idea why.

This post written By Anton Stout at UXMatters